Martina

Click here to get a full description of the infographic.

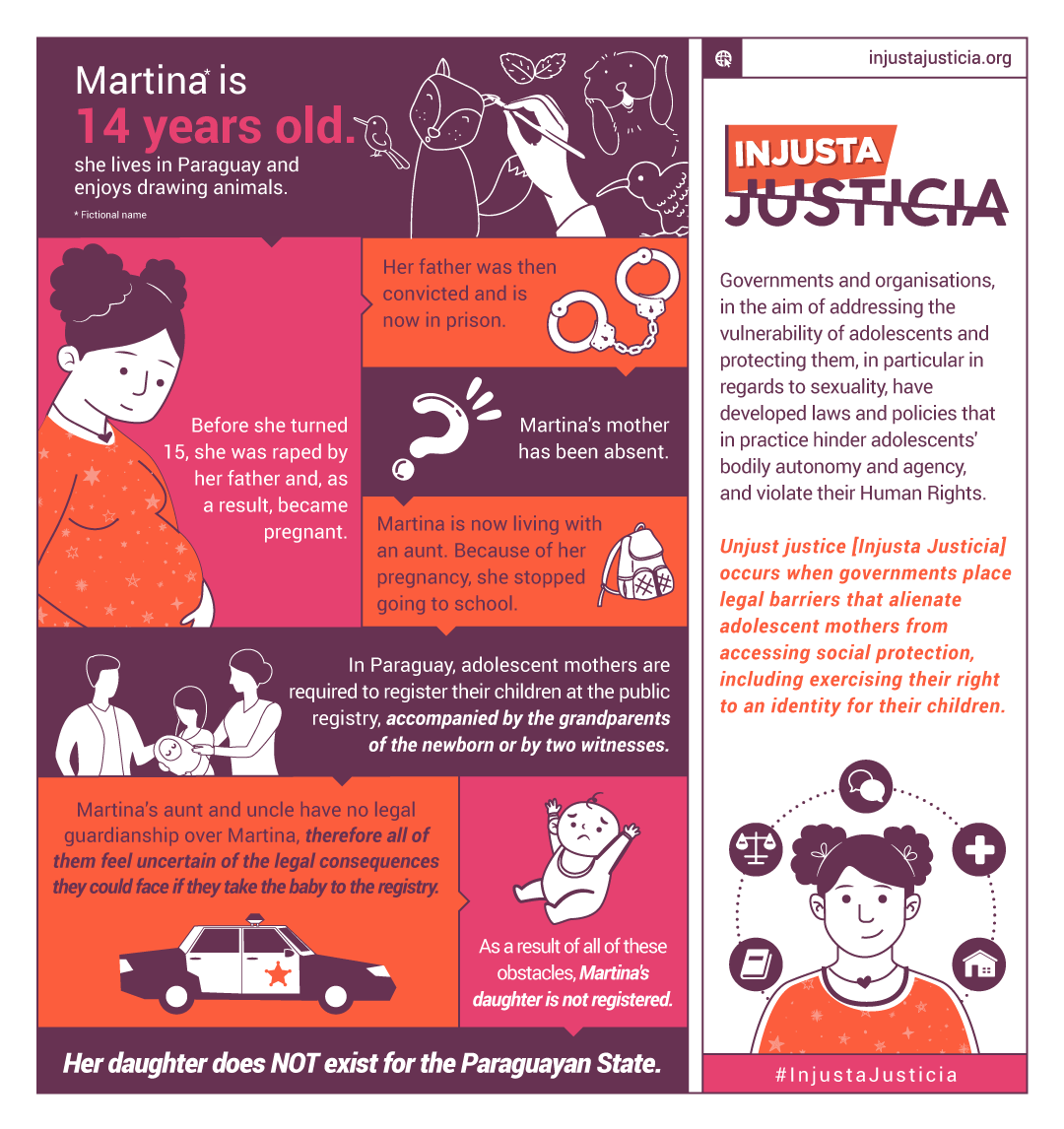

Martina gave birth to a girl. The General Directorate of the Civil Register (DGREC, for its acronym in Spanish) sets additional requirements to register the children of child and adolescent mothers, including being accompanied by the father, mother or two witnesses (resolution 64572010 of the DGREC). Since she gave birth, Martina has had very little contact with her mother, who has shown no intention to care for Martina and her daughter. The total absence of the father and the virtual absence of the mother have added to the complexity of the registration of Martina’s daughter.

Moreover, Martina’s aunt and uncle are afraid to act as her witnesses, and they have reasons not to do so. During the criminal procedure of Martina’s father, she was asked and expressed that she prefers to live with her aunt and uncle and has been with them since. However, when the criminal procedure came to an end, the state didn’t follow up to guarantee their legal guardianship as provided in the Code of Children and Adolescents (Código de la Niñez y la Adolescencia, or CNA for its acronym in Spanish, article 106). On their side, Martina’s aunt and uncle don’t have the resources to file a petition for legal guardianship.

Lastly, there is also an issue with regard to parental authority. On the one hand, the almost absolute prohibition of abortion leaves girls with the only option of giving birth. That is, the state forces them to deliver but doesn’t offer suitable conditions for them to go through motherhood. On the other hand, the Civil Code sets forth that a 14-year-old minor doesn’t have the legal capacity to have parental authority, which is only acquired with the age of majority when they turn 18 (articles 36 to 39). In practice, the legal guardianship of the child and adolescent mothers’ children falls back on their mothers and fathers (grandparents of the newborn) or another adult in the family. In other words, it is inconsistent to force girls and adolescents to give birth when they don’t have any parental authority over their children.

It is unfair that the state deems them competent to give birth but not to make decisions about how they raise their children. It is unfair that the state deems them competent to give birth but not to make decisions about how they raise their children.

Cases such as Martina’s, in which child and adolescent mothers face multiple obstacles to register their children, are common in several countries of this region. This is why in many cases, public officers themselves advise girls and adolescents – and some other times girls and adolescents decide – to wait until they come of age to make the legal registration. This is to say that it has become common for children to be registered years after birth, sometimes past their eighth birthday. Before their registration, these kids do not exist in the eyes of the state and hence don’t have any access to public services.

- In cases like this, the state must guarantee the legalization of the legal guardianship of child and adolescent mothers. This would lift a disproportionate weight on families of filing procedures before the court and avoid future complications in cases similar to Martina’s.

- A mechanism to facilitate and allow registering children from birth must be established for child and adolescent mothers. The current system, lacking measures to facilitate the process, puts an excessive burden on girls and adolescents and their families.

- It is essential to create mechanisms to allow child and adolescent mothers to register their children without any additional requirements or obstacles that hinder the process.

The Injusta Justicia campaign seeks to promote reflection on the limits of criminal law and punitivism as a defense strategy for sexual and reproductive rights, particularly those of adolescents. The campaign aims, among other things, to put the unforeseen consequences of the unrestricted application of criminal regulations and the impact this has on the autonomy and lives of adolescents under the spotlight. Injusta Justicia doesn’t have – or presume to have – all the answers but intends to inspire debate and to have the conversations we need as feminists to propose transforming strategies and alternatives focused on the survivors. We invite you to take part in this discussion.

Sexual and reproductive rights policy and regulatory framework in Paraguay:

Policies that could have an impact the lives of adolescents in the region: